Though music has been a part of the American cultural fabric since its inception, prior to the mid-19th century, the idea of marketing music to the masses was an undeveloped one. This Study Unit explores the early roots of folk music and classical music in America and how each influenced the arrival of the popular music industry. Important American composers of the 19th century are explored, giving attention to their contributions, musical styles, and how they set the stage for the explosion of popular music in the 20th century. The development of recording technology and its role as a contributory force in American popular music is also discussed. Finally, the absence, and eventual establishment, of copyright law to protect music in America is presented as a key factor in establishing the permanence of the popular music industry.

What will you learn in this unit?

- Examine the roles of folk music and classical music in early American culture.

- Understand how popular music was an amalgamation of elements of folk and classical music.

- Consider how the lack of copyright law impacted early popular music.

- Investigate the roles of important early American musicians in the evolution of popular music.

- Explore the impact of important American musicians in the 19th

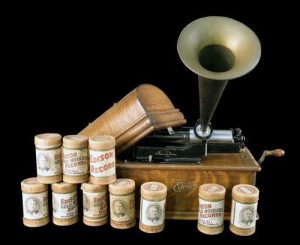

- Discuss the growth in recording technology and its role in the popularization of music in America.